What are CLOs?

Mike Peterson

20 years: Capital markets media

A CLO, or collateralised loan obligation, is a fund that owns leveraged loans. In this video, Mike not only explains what a CLO is, but what purpose they serve and how they differ from other forms of securitisation.

A CLO, or collateralised loan obligation, is a fund that owns leveraged loans. In this video, Mike not only explains what a CLO is, but what purpose they serve and how they differ from other forms of securitisation.

What are CLOs?

11 mins 28 secs

Key learning objectives:

Define what a CLO is

Understand the CLO investor base

Define the role of a CLO manager

Overview:

A CLO, or a collateralised loan obligation, is a type of fund that owns leveraged loans. They differ from CDOs in the type of asset that backs the security, and exists as an option for risk averse and yield hungry investors alike.

What are CLOs?

A CLO, or a collateralised loan obligation, is a fund that owns leveraged loans. It raises the money it needs to buy the loans by issuing different classes of notes, and these usually have credit ratings. The loans act as security for the CLO notes. So, in this sense, a CLO is a kind of securitisation. Unlike most other kinds of securitisation, however, a CLO has a manager, a firm whose job it is to choose which loans to buy. A CLO is usually actively managed: the manager can buy and sell loans, subject to various pre-agreed restrictions, during at least some part of the life of the CLO.

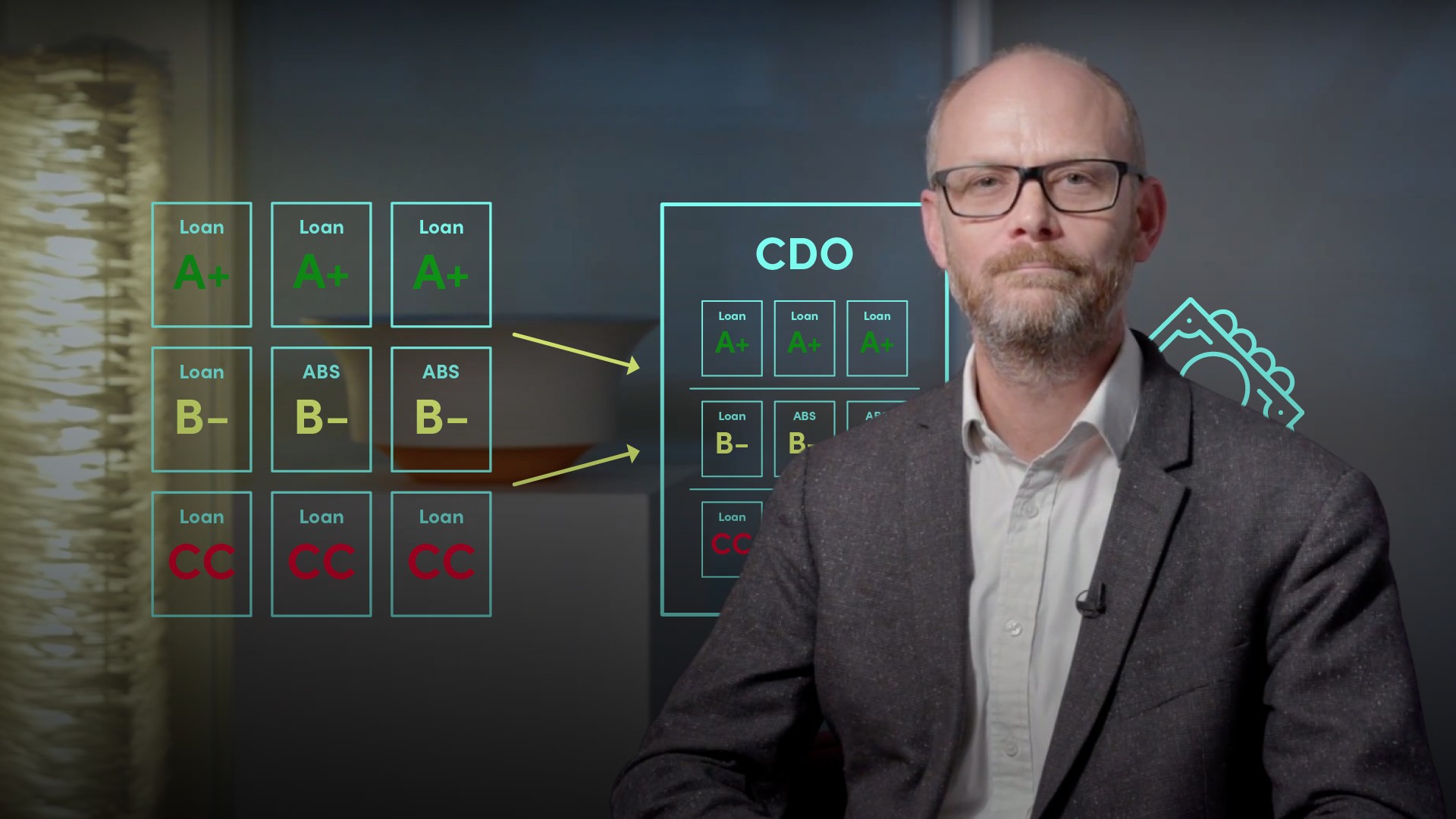

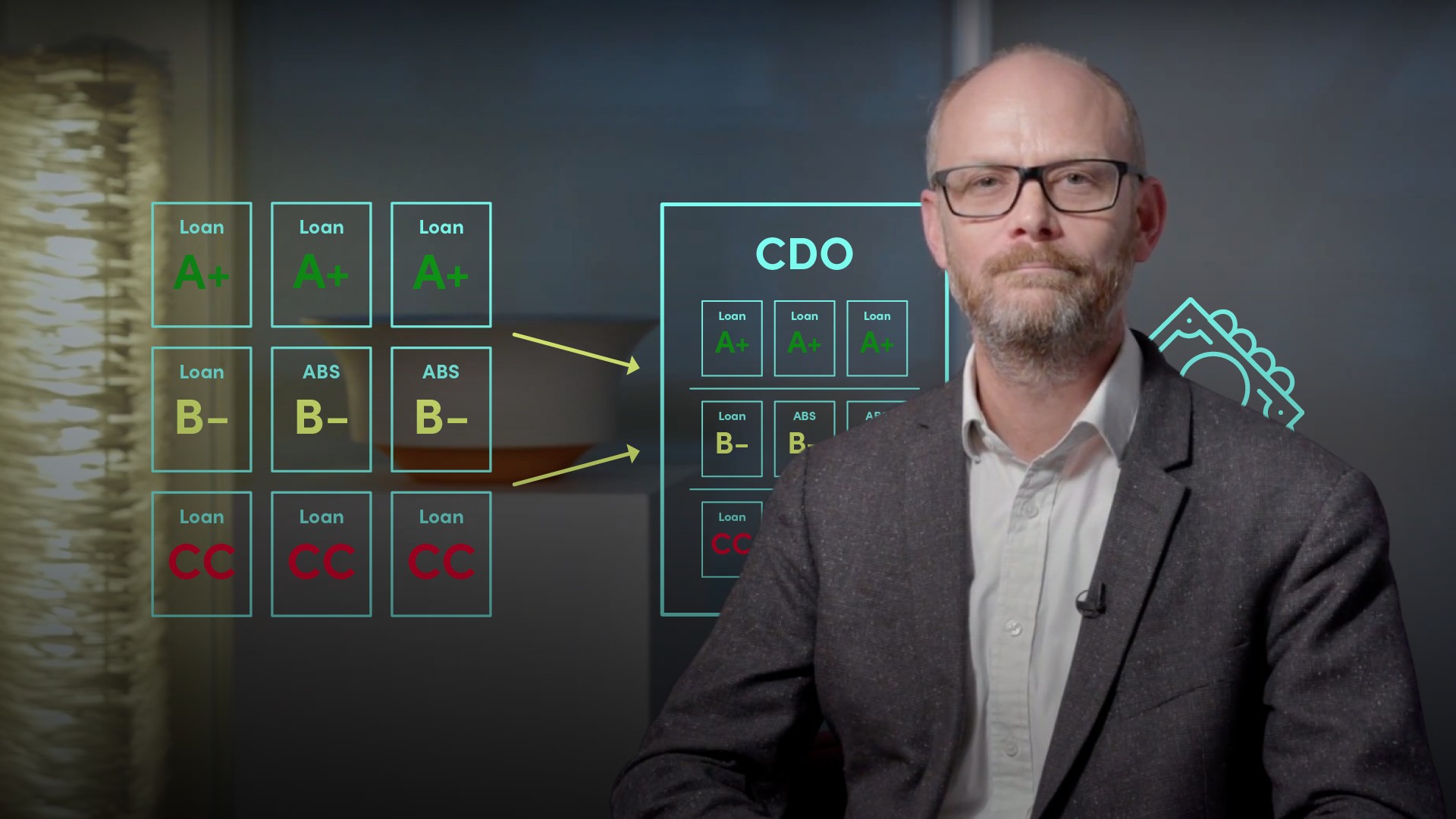

How are CLOs different to CDOs?

Many CLO market practitioners today are adamant that CLOs bear no resemblance to the kind of CDOs that led to the financial crisis, other than having a similar name.

This is true, in part. One big difference is performance. Whereas many investors in CDOs of subprime mortgages lost money during and after the crisis, CLOs ultimately performed extremely well. The difference in performance can be explained by the performance of the kind of assets that these vehicles owned. The assets that went into CDOs were asset-backed securities, including subprime mortgage-backed bonds. And these assets suffered much higher losses than anyone before the financial crisis had expected.

CLOs, by contrast, own leveraged loans, that is, loans to large US and European companies. Some of these companies were hurt by the credit crunch, and defaulted on their loans. But the level of losses overall was in line with historical predictions. So, CLOs in turn, suffered only small losses.

Why do CLOs exist?

They exist for the same reason that any kind of securitisation exists. Pooling and tranching financial investments can make them appeal to groups of investors who would not buy them otherwise. That creates extra buying power for that particular financial investment, and encourages more of it to be created.

CLOs can take investments from very risk averse investors, very yield-hungry investors and investors in between. Blended together, those different classes of investors have sufficient demand for loans that it is often possible to achieve what is commonly referred to as an arbitrage or funding gap. This means that after buying the portfolio of loans and paying the different classes of investors the returns they demand, there is still enough money left over to pay a fee to the firm that created and runs the CLO. That firm is known as the CLO manager.

What is the importance of the manager?

One of the biggest differences between CLOs and other forms of securitisation is the manager. Most securitisations pool and tranche long dated assets. But loans are much shorter in life. They usually mature in only a handful of years, and the companies that issue them frequently decide to pay them back early. So CLOs need somebody, the manager, to decide which new loans to buy when old ones get repaid.

In practice, CLOs often buy and sell loans frequently, not just when loans repay. It is not unusual for a manager to change the composition of a CLO portfolio 100% over the course of a year. Typically, CLO managers see their role as one of boosting returns for investors through smart buying and selling decisions. It is rather like managing a hedge fund. And many managers regard CLOs as just one other type of fund in a suite of asset management products including hedge funds, private equity funds, separate accounts and mutual funds.

Mike Peterson

There are no available Videos from "Mike Peterson"