CLOs as an Asset Class During the GFC

Ian Robinson

25 years: Securitisation

In Ian's final video on CLOs, he takes elements discussed in his previous two videos and explains how these factors played out during the financial crisis.

In Ian's final video on CLOs, he takes elements discussed in his previous two videos and explains how these factors played out during the financial crisis.

CLOs as an Asset Class During the GFC

10 mins 36 secs

Key learning objectives:

Identify how CLOs performed, and the impact this had on various counterparties

Outline the role of rating agencies during this time

Understand the overall impact liquidity had on the CLO market

Overview:

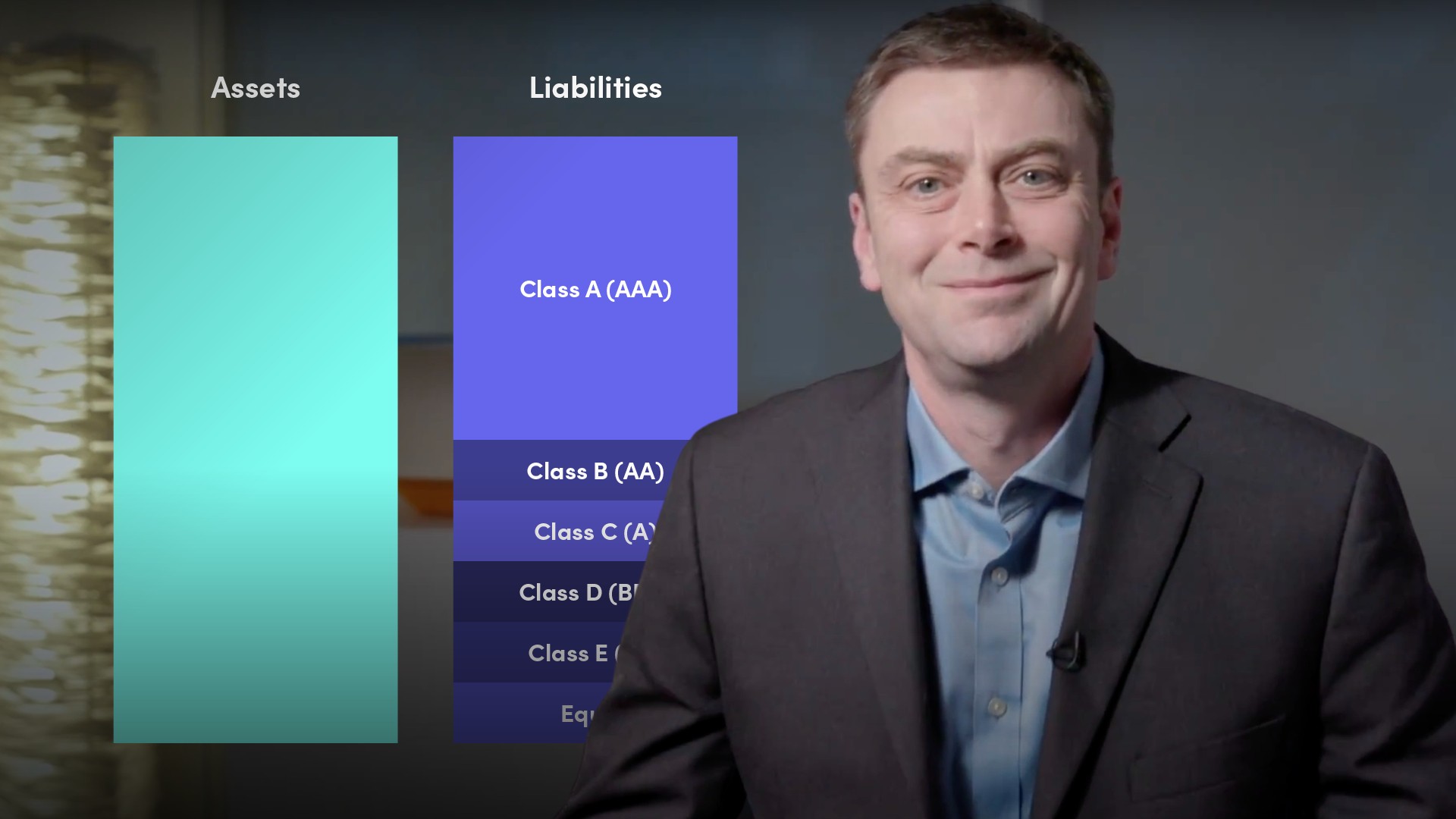

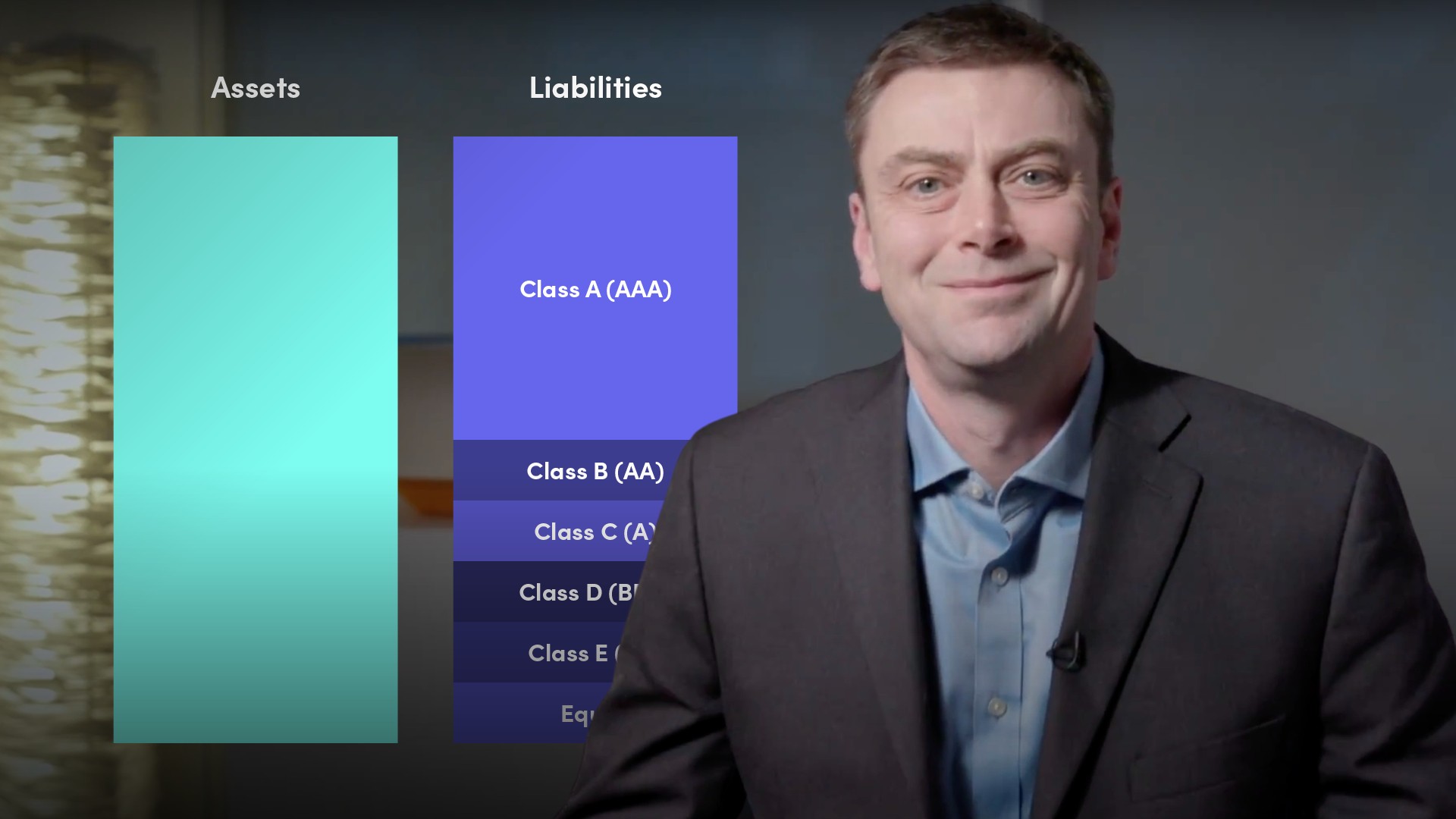

In the summer of 2007, liquidity, credit and market risk posed a significant threat to the CLO market. CLOs held up relatively well during the crisis, however, the losses that did occur, were caused almost entirely by investors not having access to term funding.

What was the atmosphere in October 2007?

By October, CLO collateral managers attempted to raise low levered funds as they realised that traditional full capital structure CLOs were no longer possible to issue. Along with this, numerous small institutions and asset managers that were running out of money were taken over in the hope that they could survive.Did liquidity hold up in the CLO Market?

When a bank is confident that it can get hold of more cash, it will lend out the cash it has in hand. When conversely the bank is concerned about their cash position, it will hold on to that cash, having a knock on effect on its customers and counterparties.

During the crisis, liquidity in the secondary market for CLOs dried up, and the yield to maturity on, for example, Triple A bonds moved from approximately 25 basis points, out to 200 basis points.

Why was holding CLOs at this time difficult?

For those in charge of running a fixed income portfolio of illiquid assets such as CLO bonds, there was no easy way to find a price. Therefore, in order to mark-to-market the portfolio, each month there was a long winded method of asking for bid levels from traders in banks. During this time, the bids from banks used for mark-to-market purposes were much lower than before given the general lack of demand. This led to further valuation reductions, which led to further redemption requests that could not be met, and thus led to more gated funds or more forced selling.

Bids from banks were also used to calculate the collateral due under repo payments. Not only did banks not want more CLOs, but they were also incentivised to reduce further their birds in order to force unwinds of repo agreements as they are struggling to borrow from other banks and wanted to hoard cash.

What initiatives did banks take?

Bank traders were told to reduce Value at Risk (VaR), because it is based on volatility, as the YTM of the bonds increased rapidly, so did the VaR measure, meaning that the banks, who until then had been the main provider of liquidity in the CLO market, all but stopped buying bonds entirely. When they did buy bonds, it was at vastly reduced prices. The reason being, they worried that no-one would have any cash to buy it from them at any point in the near future, they would then be stuck with an illiquid assist on their trading book indefinitely.

Banks refused to lend to each other, and this represented their concerns about whether they could meet their obligations. A clear example of this was Northern Rock in the UK who had a large book of 25+ year mortgages as assets which were funded from the commercial paper market. When this commercial paper wasn’t renewed, there was a run-on-the-bank.

How did Rating Agencies impact CLOs?

During this period, there were a lot of rating agency downgrades, particularly due to their mishap in rating numerous banks such as Fannie Mae, Freddie Mac, AIG and Lehman Brothers Triple A. These banks however, defaulted or had to be rescued. In order to ensure this mistake wasn’t repeated, rating agencies reacted aggressively by downgrading hundreds of tranches at a time. The downgraded tranches forced more selling from funds that could only hold investment grade bonds.

The rating agencies also downgraded the underlying leveraged loans. Asking for a bid on a CCC leveraged loan in 2007/08 did not bring a high price. As the portfolios were marked down, many of them breached their over-collateralisation tests.

What impact did the YTM and Macaulay Duration have on CLO prices?

The MD on bonds had been extended massively at the same time that the general YTM for sub-investment grade highly leveraged companies skyrocketed. This combination meant that:- Prices of CLO bonds plummeted and stayed low

- Every time things quietened down, another default of a large financial institution would either, scare an investor, or take another chunk of liquidity out of the market

How were CLOs performing post-September 2008?

By the time the Lehman Brothers failed in September 2008, you could buy the subordinated tranches of CLOs at option value, e.g. 5-8 cents in dollar, and some Triple A bonds were trading less than 70 cents in the dollar. At this point, the market risk was largely gone from the CLO market on the basis that the price was so low, it was hard to see it going further.

It took a few years for the backlog of bonds to clear through the market. Every time a fund had to close, there was a large auction which flooded the market with more bonds at distressed prices, keeping the overall market price low. In relation to CLOs, very few, (approx 15) transactions in Europe ended up making losses for those junior investors that held on to the bonds.

Ian Robinson

There are no available Videos from "Ian Robinson"