Time Lags and the Multiplier Effect

Tim Hall

30 years: Debt capital markets

In the first two videos of this series Tim explained us the macroeconomic fundamentals of fiscal policy. In this video he will highlight some of the issues that make fiscal policy challenging for governments, since the theoretical outcome often differs from reality.

In the first two videos of this series Tim explained us the macroeconomic fundamentals of fiscal policy. In this video he will highlight some of the issues that make fiscal policy challenging for governments, since the theoretical outcome often differs from reality.

Time Lags and the Multiplier Effect

8 mins 5 secs

Key learning objectives:

Explain time lags, as well as how and why time lags can affect the implementation of discretionary fiscal policy

Explain how multipliers can affect the potency of discretionary fiscal policy

Overview:

Discretionary fiscal policy is far from perfect because there are often significant and unpredictable time lags involved, and the magnitude of a particular policy tool on GDP is often difficult to predict because of multipliers. Having said this, time lags and multipliers have been observed over time and are fairly well understood even if not always perfectly predictable. Time lags refer to the fact that discretionary fiscal policy tools used by governments take time to generate the targeted counter-cyclical results. Multiplies mean that the amount of fiscal stimulus needs to be carefully calibrated in terms of the targeted effect.

What are time lags?

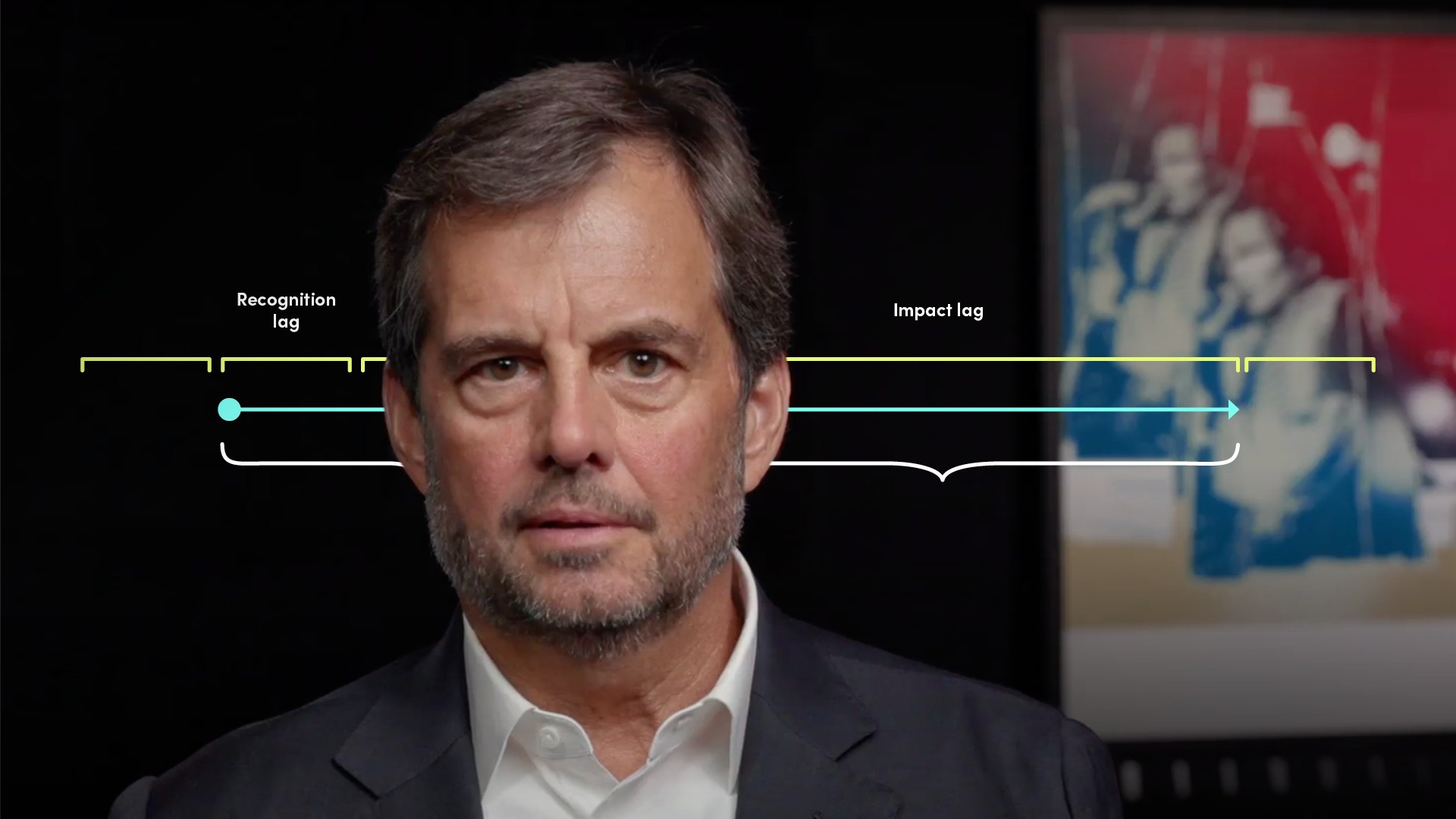

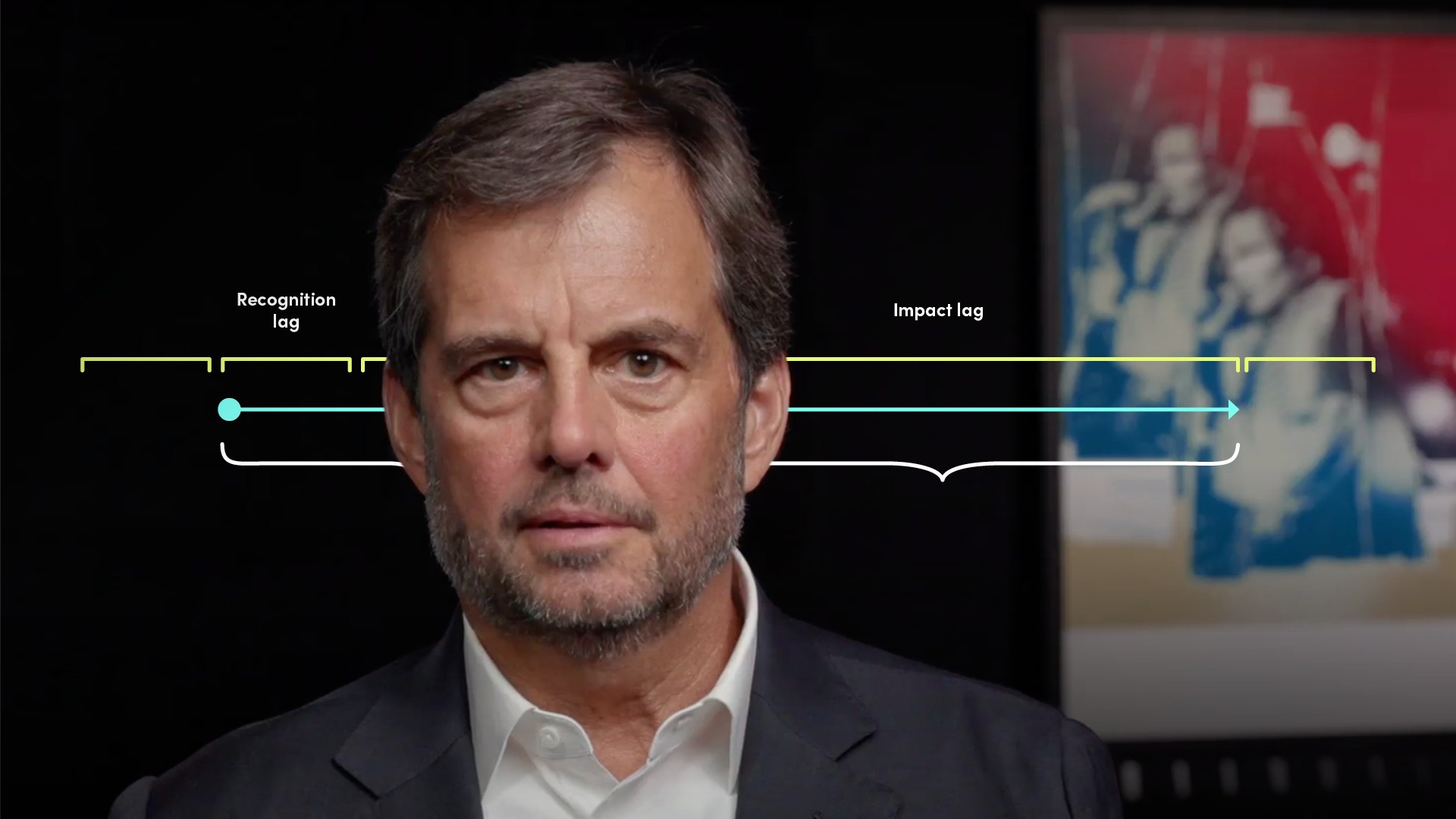

Time lags refer to the period of time from when an economic imbalance is first recognised and acknowledged until the time that a chosen fiscal policy tool achieves its desired result. Economists believe that the total time can range from one to two years.

What are the components of time lags, and how long does each take?

Time lags consist of inside policy lags (three) and an outside policy lag. The three inside policy lags – recognition, decision and implementation lags – refer to the collective time between when an economic imbalance is recognised and an action plan is formulated and implemented.

The outside policy lag, or the impact lag, is the time it takes for a given policy response, once implemented, to adequately address the imbalance and restore the economy to equilibrium.

What are multipliers, and how do they affect fiscal policy?

The multiplier effect refers to how a given fiscal policy affects GDP once it has been introduced into the economy. Every fiscal policy tool has a multiplier effect, meaning that one unit of change in taxes or in government expenditures has more than a one unit effect on economic growth.

Are multipliers the same for taxes and government spending?

No. Increases (decreases) in government spending have a higher multiplier effect than tax decreases (increases). The reason is that every unit of incremental government spending flows into an economy, whilst not every unit of a tax decrease similarly flows into an economy. When consumers realise more disposable income because of tax cuts, they often choose to save some of the marginal increase (rather than spend it) because of uncertainty. This reduces the multiplier, or potency, of tax policy compared to government spending. When there are tax cuts, the amount not spent by consumers is referred to as “leakage” The higher the leakage, the lower the multiplier.

What has the COVID-19 fiscal stimulus meant for time lags and multipliers?

In a nutshell, because the COVID-19 recession was in essence manufactured by governments since it was foreseen, the time lags were shortened considerably as governments moved quickly to provide fiscal support for economies, large parts of which were shuttered. As far as multipliers, people receiving fiscal stimulus were certainly not able to spend all of their government-provided aid, either because large parts of economies were closed (and many, e.g. travel, remain difficult), or because people chose to save some or all of their aid rather than spend it because of the uncertain future associated with the pandemic. This reduced the multiplier effect.

Tim Hall

There are no available Videos from "Tim Hall"