What is a Leveraged Buyout (LBO)?

Tim Hall

30 years: Debt capital markets

Leveraged buyouts, or 'LBOs', can at times provide investors with high returns despite only risking little relative capital. In this video, Tim details the role of leverage within the process as well as describing appropriate capital structures.

Leveraged buyouts, or 'LBOs', can at times provide investors with high returns despite only risking little relative capital. In this video, Tim details the role of leverage within the process as well as describing appropriate capital structures.

What is a Leveraged Buyout (LBO)?

20 mins 6 secs

Key learning objectives:

Define a leveraged buyout

Understand how leverage can maximise returns

Know the types of debt used in an LBO and the importance of capital structure

Overview:

Perpetual bonds are a hybrid debt instrument that possess similarities with bonds and equity. The key feature of a perpetual bond is that there is no maturity date. The benefit of issuing a perpetual bond for a company is that it lowers their debt leverage. For an investor, it often offers a higher yield than other forms of debt on the market.

What is a leveraged buyout?

LBO, an acronym for “leveraged buyout”, refers to the acquisition of a company using a significant amount of debt, which can be in the form of bank loans, 2nd lien loans, high yield bonds, mezzanine loans or a combination thereof. I’ll explain these terms a little later. In nearly all cases, the buyer of the target company is a private equity firm, also commonly referred to as a financial sponsor.

What is the role of leverage?

| (all in $000's) | |||

| Purchase price of the company | 100,000 | ||

| Company value at sale, 5 years from now | 200,000 | ||

| 3 scenarios to finance purchase | Scenario 1 | Scenario 2 | Scenario 3 |

| Cost of company at purchase | 100,000 | 100,000 | 100,000 |

| Scenario description | No leverage | Light leverage | High leverage (LBO) |

| Debt | 0 | 25,000 | 75,000 |

| Equity | 100,000 | 75,000 | 25,000 |

| Total cost at purchase | 100,000 | 100,000 | 100,000 |

| Value of company at sale, five years | 200,000 | 200,000 | 200,000 |

| Value of equity at sale (value less debt) | 200,000 | 175,000 | 125,000 |

| Times Equity Earned at Sale | 2 | 2.3 | 5 |

| Annualised Return on Equity | 14.90% | 18.50% | 38.00% |

As you can see, as the amount of leverage used increases, the equity earned at sale increases dramatically. This is the fundamental intuition behind an LBO.

What makes a good LBO candidate and how are they valued?

- Strong and steady cash flows

- Non cyclical business

- Low disruption risk from new technologies

- Strong management team

- Efficiency and flexibility

Once a financial sponsor determines the enterprise value, it turns its attention to designing the appropriate capital structure that will enable it to maximise its return whilst not putting the newly-leveraged company at too much risk if things don’t go as expected. The capital structure – or mix of debt and equity – obviously varies from situation to situation depending on some of the attributes mentioned above.

What is the appropriate capital structure?

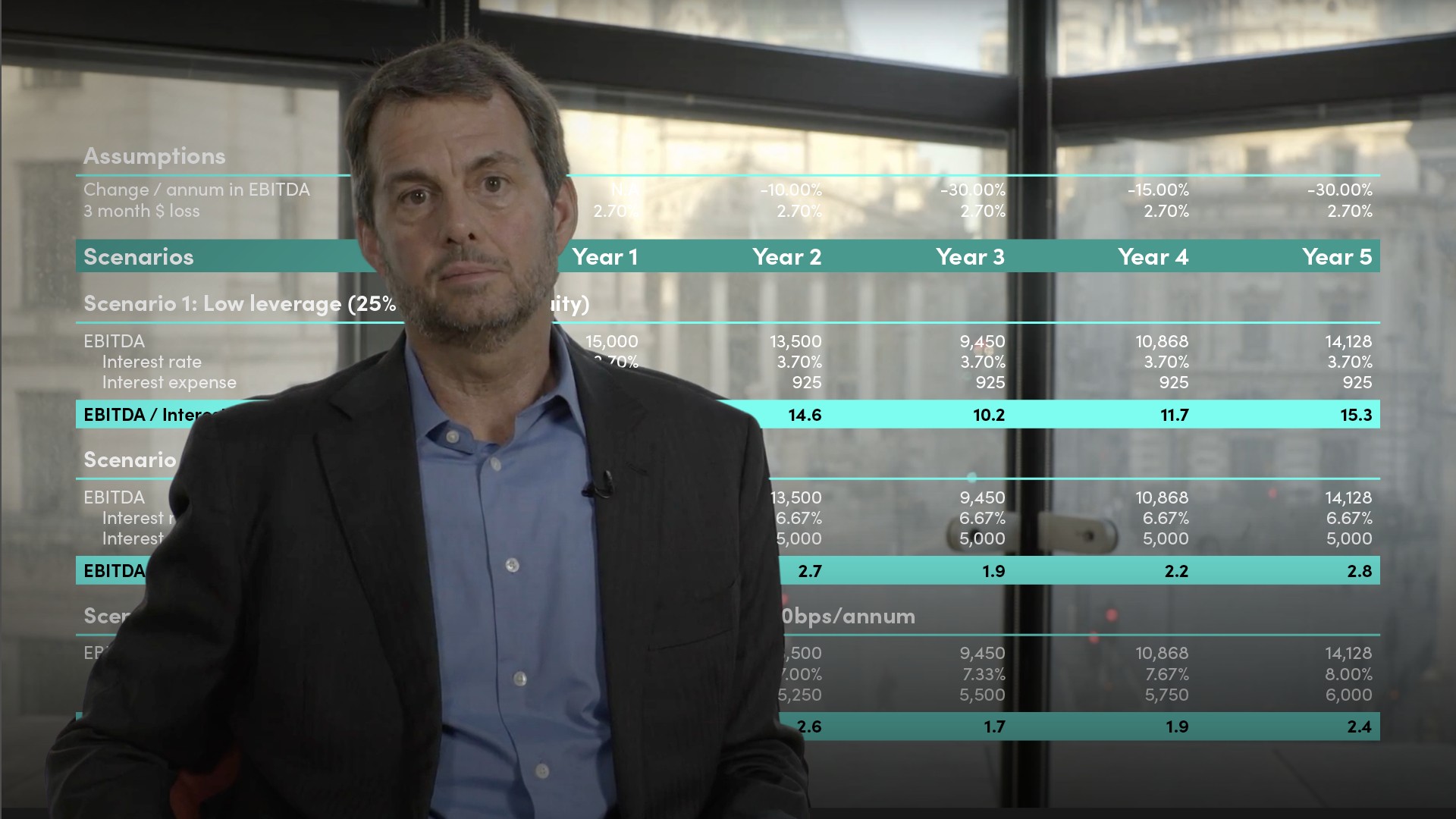

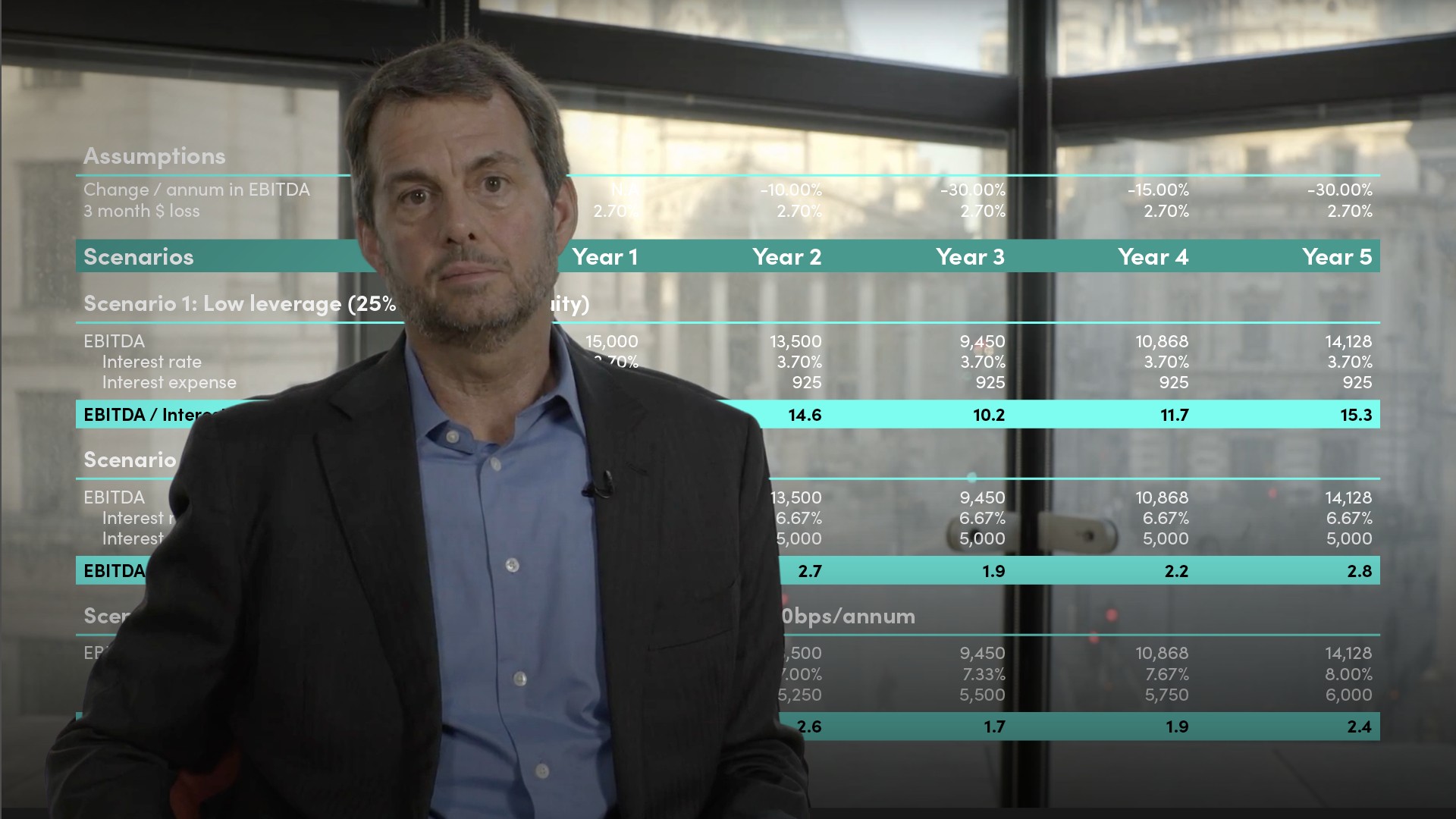

From a lender’s perspective, the appropriate capital structure also has to be determined. Lenders will likely be more conservative than private equity investors in most situations. To determine the appropriate amount of debt, lenders will compare the proposed transaction to other recent LBO’s, and importantly, will also aim to get a flavour for current investor sentiment for leveraged transactions. Potential lenders will develop their own projections, which most certainly will include a downside – or stress case – scenario. The typical total debt-to-EBITDA in an LBO is between 5.0x and 6.5x, which is aggressive by historical standards but is indicative of the large number and variety of investors that are currently searching for higher yielding assets. The amount of the purchase price contributed as equity is normally between 25% and 35%.

The acquisition debt in an LBO is normally divided into senior secured facilities provided by banks, and a junior – or subordinated - debt layer, which could be a 2nd lien loan, a public unsecured high-yield bond or a privately-placed mezzanine loan. The senior debt is secured and is normally provided by a group of three to seven lead banks – depending on the size of the transaction. These lead banks underwrite and then distribute – or syndicate - the senior debt facilities to other banks and to institutional investors.

The junior tranche in an LBO transaction is generally underwritten by the same bank group providing the senior secured debt financing, in the form of a subordinated bridge loan. The intention is for the subordinated bridge loan to be entirely refinanced after the transaction closes as a 2nd lien loan or as a public high yield bond, both targeted at institutional investors. A 2nd lien loan – as the name suggests – would have a 2nd lien on the assets of the company, whilst a high yield bond would be unsecured. 2nd lien loans are normally floating-rate, which provides early prepayment flexibility, whilst high yield bonds are normally fixed-rate, with 3 to 4 years of “hard call protection”, meaning that they cannot be repaid during this period.

The private mezzanine market is also used from time to time to provide the subordinated tranche in an LBO. These loans are privately placed with one or a small consortium of mezzanine lenders. The mezzanine lender is involved from the onset of a transaction working along the banks, eliminating the need for a subordinated bridge loan altogether. Mezzanine loans can serve as a natural solution for the subordinated tranche of smaller LBO’s, in which a 2nd lien loan or a high yield bond are not viable alternatives because the need is too small.

One final point regarding the capital structure of an LBO is that various public and private market instruments, essentially hybrids between debt and equity, can be slotted between the 2nd lien note or high yield bond, and the equity, to permit additional leverage on the contributed equity. The public market alternative would be a junior subordinated bond, which often has a pay-in-kind – or PIK - feature.

Tim Hall

There are no available Videos from "Tim Hall"